LightRocket via Getty Images

Last week, the Network for Greening the Financial System (NGFS), a global collective of nearly 100 central banks and supervisors, released their much-anticipated new climate scenarios. Originally developed for policymakers, climate scenarios have also become important for financial actors. Recognizing the threats to financial stability posed by climate change, regulators are using scenarios to assess the financial sector’s climate resiliency. Financial institutions are not only conducting climate scenario analysis to meet regulatory demands, but also to identify future risks and opportunities. As firms commit to decarbonization, climate scenarios provide pathways for reaching net-zero greenhouse gas emissions. Climate scenarios also offer insights for governments and corporations looking to prepare for a sustainable future.

NGFS 2021

Given the large number of climate scenarios and their rising relevance for financial decision-makers, in May 2020, the NGFS partnered with leading climate research institutions to develop common reference scenarios. These reference scenarios were well-received, but it was acknowledged that continual enhancements would be required to meet the needs of scenario users.

These second-generation scenarios offer new storylines that more closely reflect the current climate policy environment and the goal of net-zero carbon dioxide emissions by 2050. In addition, the scenarios incorporate the latest economic and energy developments, resulting in higher forecasts for renewables deployment and more conservative assumptions regarding negative emissions technologies. The scenarios also have become more detailed and comprehensive, with improvements to both sectoral and geographic granularity. Finally, the scenarios more fully explore the economic implications of climate change and the impacts of physical hazards. The subsequent sections explore the structure and storylines behind these new scenarios and what they mean for financial actors.

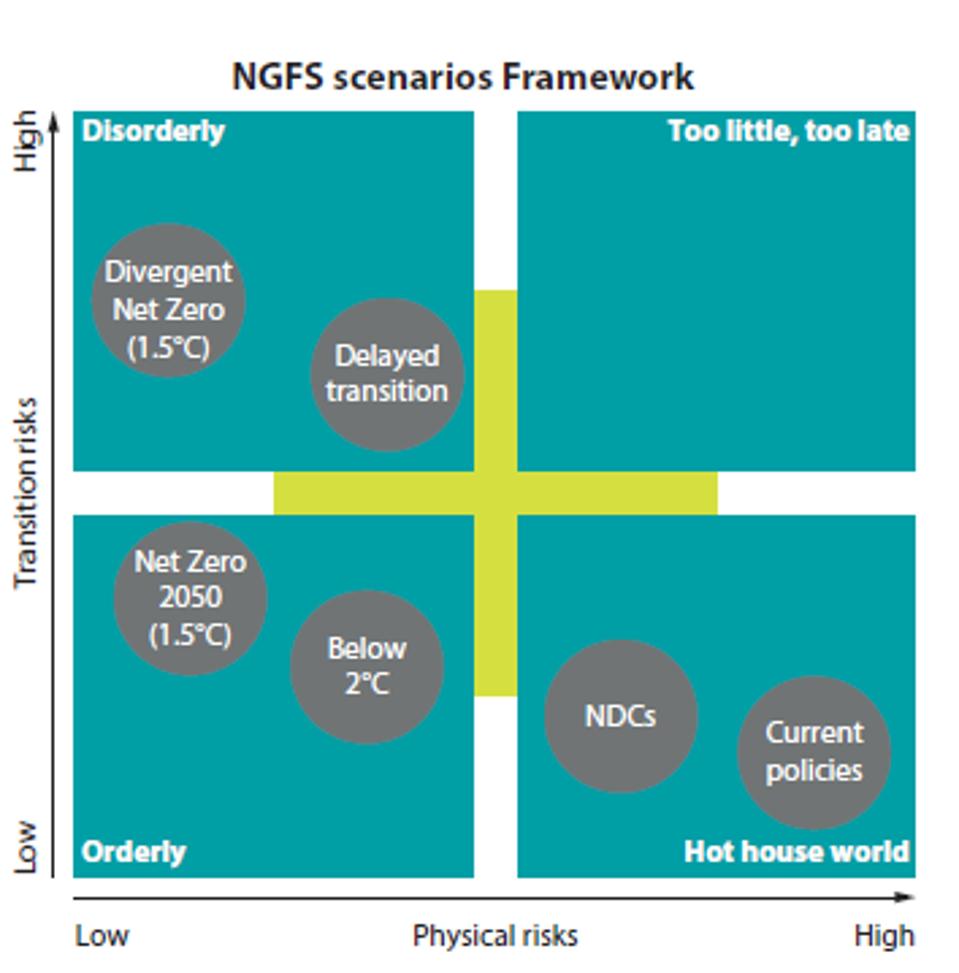

The NGFS scenario framework evaluates climate scenarios on two axes, transition risks and physical risks.

NGFS 2020

MORE FOR YOU

To some extent, there are tradeoffs between the two risk types. As an example, if the world pursues ambitious climate action and rapidly cuts emissions, that will demand major changes across economic sectors (higher transition risks), but temperatures will rise less, and so climate impacts will be less severe (lower physical risks). With this two-by-two matrix of risks, the NGFS scenario framework categorizes scenarios as follows:

- Orderly scenarios (lower physical risks, lower transition risks)- such pathways assume that global climate action begins quickly and escalates in a steady but consistent manner. This is best for economies and the planet.

- Disorderly scenarios (lower physical risks, higher transition risks)- such pathways see significantly higher transition risk because although significant climate action occurs, it may be delayed, piecemeal, or abrupt.

- Hot house world scenarios (higher physical risks, lower transition risks)- such pathways assume some climate action takes place, but not enough to reach global climate goals, resulting in a world beset by damaging climatic events.

- Too-little too-late scenarios (higher physical risks, higher transition risks)- such pathways see aggressive and abrupt climate action only after warming has occurred, causing higher physical and transition risks.

As in the first generation of NGFS scenarios, these new scenarios fall into the orderly, disorderly, or hot house world categories. However, the scenario storylines have been updated significantly to reflect the latest climate goals, climate policies and economic data. By category, these new scenarios are:

Orderly

- Net Zero 2050- strong climate policies and green innovation efficiently reduces carbon dioxide emissions to net-zero by 2050. Global warming is limited to 1.5?C.

- Below 2?C- a more gradual (but still steady) rise in climate policy ambition. Global warming has a 67% chance of being kept below 2?C.

Compared to the previous orderly scenarios, the new orderly scenarios include additional breakouts for countries and regions and assume lower levels of negative emissions technology use.

Disorderly

- Divergent Net Zero- another pathway to net-zero, but with higher transition risks (rapid oil phase out) and economic costs due to varied policies introduced in different regions at different times. Global warming is limited to 1.5?C.

- Delayed Transition- strong climate action is delayed until 2030, so aggressive policies are needed thereafter and there is limited use of negative emissions technologies. Warming is likely limited to just below 2?C.

Compared to the previous disorderly scenarios, the new disorderly scenarios explore the impacts of distinct regional policies and the effects of different carbon prices across economic sectors.

Hot House World

- Nationally Determined Contributions (NDCs)- this pathway assumes that all policies pledged by governments are implemented, but no additional ones. Global warming is likely around 2.5?C.

- Current Policies- this is the least ambitious climate scenario as currently implemented policies are the only climate policies considered. As a result, a slow and incomplete transition leads to more severe physical risks. Global warming may be above 3?C.

Compared to the previous hot house world scenarios, the new hot house world scenarios forecast lower emissions and lower temperature rises. These updates reflect energy transition already underway, stronger new climate policies, and new economic forecasts post-COVID-19.

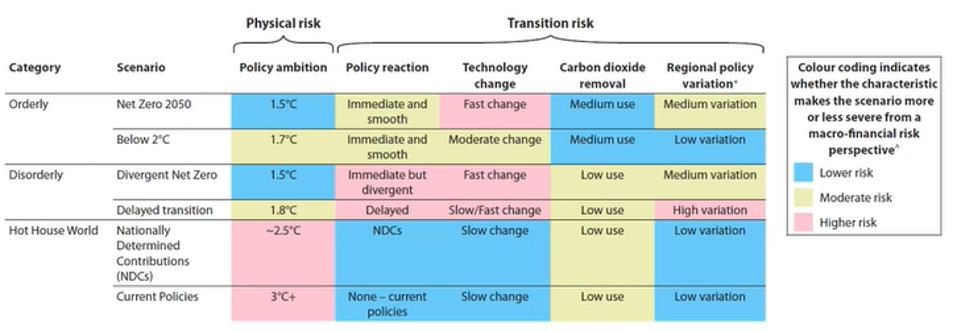

Given the increasingly prominent role of climate scenarios in risk management and risk assessment, scenario users must understand the key risk drivers within each pathway. These risk drivers are scenario specific characteristics that may increase transition or physical risks. In this second generation of scenarios, the NGFS called out five characteristics that may influence the severity of a given storyline. One characteristic pertains to physical risk severity, while four pertain to transition risk severity. They are:

- Policy ambition (physical)- the higher the policy ambition, represented by a lower final temperature, the lower the physical risk.

- Policy reaction (transition)- the more delayed or disjointed the policy action, the greater the potential transition risk, especially for high ambition scenarios. Transition risk is lower in low ambition scenarios, which also have relatively limited policy actions.

- Technology change (transition)- the faster technologies evolve; the economic disruption experienced by incumbent firms. However, new technologies will also make it easier to reach global climate goals.

- Carbon dioxide removal (transition)- the more negative emissions assumed, the less deep and dramatic emissions cuts need to be, reducing transition risk. However, the feasibility of massive negative emissions has been increasingly questioned by the scientific and policy community.

- Regional policy variation (transition)- the more variation in regional policies, the greater potential for uneven decarbonization and economic disruption, increasing transition risk.

The table below shows how the scenarios incorporate these five characteristics and the ramifications for physical and transition risks.

NGFS 2021

In the coming months, these new NGFS scenarios will be adopted by many in the financial sector. Regulators will use them to design industry-wide scenario analysis exercises or stress tests. Institutions will use the scenarios to set decarbonization targets, evaluate climate-related financial risks, and make TCFD (Task force on Climate-related Financial Disclosures) disclosures. Policymakers and corporate leaders will also use the scenarios to determine climate and transition risks in their regions and sectors. This second generation of scenarios gives these stakeholders an expanded set of tools for evaluating climate impacts and pathways to a sustainable future.

The next article will explore the financial sector implications of the scenarios’ major assumptions.

/https://specials-images.forbesimg.com/imageserve/60c7b043b31603dca279804f/0x0.jpg)