I have no idea whether the stock market is actually forming a bubble that’s about to break.

But I do know that many bulls are fooling themselves when they think a bubble can’t happen when so many of us are concerned about one. In fact, one of the distinguishing characteristics of a bubble is that such concern is widespread.

This seems counterintuitive. You would think that a bubble is most vulnerable to forming and then popping when investors are oblivious to that possibility. But you would be wrong.

It’s important for all of us to be aware of this bubble psychology, but especially if you’re a retiree or a near-retiree. That’s because, in that case, your investment horizon will be shorter than for those who are younger, and you therefore are less able to recover from the deflation of a market bubble.

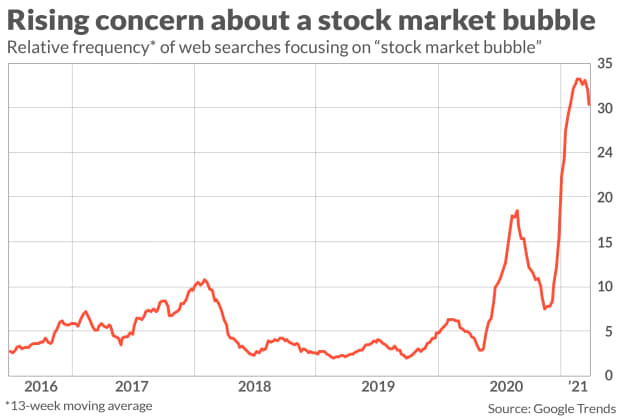

To appreciate how widespread current concern about a bubble is, consider the accompanying chart of data from Google Trends. It plots the relative frequency of Google searches based on the term “stock market bubble.” Notice that this frequency has recently jumped to a far-higher level than at any other point over the last five years.

This widespread concern is entirely consistent with a bubble’s formation, according to a definition proposed several decades ago by Robert Shiller, the Yale finance professor and Nobel laureate. According to him, a bubble is “a market situation in which news of price increases spurs investor enthusiasm which spreads by psychological contagion from person to person, bringing in a larger and larger class of investors, who, despite doubts about fundamental value, are drawn to the investment partly through envy of others’ successes and partly through a gambler’s excitement.” (I italicized the above phrase, not Shiller.)

Notice that recognition of overvaluation is an integral part of the definition.

This recognition was certainly present during the weeks and months prior to the popping of the Internet bubble in March 2000. During the early and middle years of the 1990s, you may recall, it was possible to justify higher prices while keeping a straight face. But that became less and less possible as prices continued going higher in the late 1990s, and especially as some dot-com companies went public with huge valuations despite having no assets, revenue or business plan.

Rather than responding by taking some chips off the table, however, many began freely admitting that a bubble was forming. They no longer tried to justify higher prices on fundamentals, but began justifying it instead in terms of the market’s momentum. Prices should keep going up as FOMO seduces more and more investors to jump on the bandwagon.

There is no shortage of current analogies, of course. Take dogecoin, which was created as a joke and has no fundamental value. As a recent Wall Street Journal article outlined, the dogecoin “serves no purpose and, unlike Bitcoin, faces no limit on the number of coins that exist.” Yet investors are flocking to it, for no other apparent reason than it has already gone up so much. Billy Markus, the co-creator of dogecoin, was quoted in that Wall Street Journal article saying “This is absurd. I haven’t seen anything like it. It’s one of those things that once it starts going up, it might keep going up.”

Needless to say, things don’t go up forever. Those who nevertheless continue to invest in such an environment do so with the implicit assumption that they will be able to recognize it, in advance, when the bubble is about to pop—and therefore able to leave the party before everyone else. This is a dangerous delusion, however; not everyone can be the first to leave the party.

The bottom line? Far from being a reason why a bubble isn’t forming, the widespread current concern about a possible bubble is actually a reason to worry that it could be. Take heed.

Mark Hulbert is a regular contributor to MarketWatch. His Hulbert Ratings tracks investment newsletters that pay a flat fee to be audited. He can be reached at mark@hulbertratings.com